Here’s what Merrick Garland might have been thinking.

Merrick Garland must miss the D.C. Circuit right now.

At the start of 2021, Merrick Garland was one of the most highly regarded members of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, second only to the U.S. Supreme Court in power and prestige. Although his 2016 nomination to SCOTUS was never considered by the U.S. Senate, it reflected the high esteem in which he was held, and even the Republican senators who refused to consider his nomination had only positive things to say about his credentials, intellect, and integrity. When President Joe Biden nominated Garland to serve as the 86th Attorney General of the United States, he was confirmed by a vote of 70-30—overwhelming bipartisan support in these polarized times.

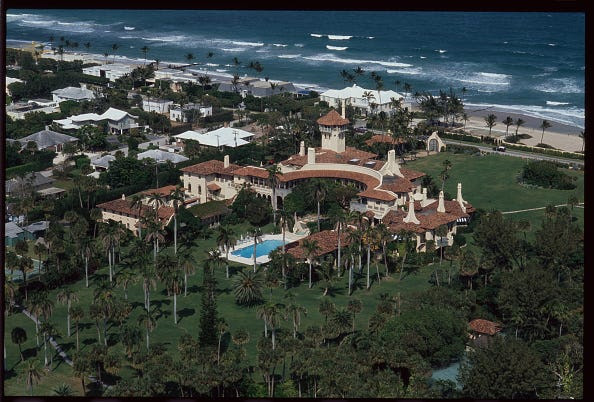

But after heeding that call to service, Garland now finds himself embroiled in the biggest controversy of his long and eventful career. On Monday, agents from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) executed a search warrant at Mar-a-Lago, the private club in Palm Beach that former president Donald Trump calls home—and since that time, Garland has received no shortage of criticism for approving the search. If Republicans retake the House of Representatives, expect hearings; as House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Cal.) tweeted on Monday night, “Attorney General Garland: preserve your documents and clear your calendar.”

What was Garland thinking? Here are some thoughts—admittedly speculative, since neither Garland nor the DOJ has said anything publicly about Monday’s search, not even officially confirming that he signed off on the warrant.

But first, a quick caveat: I presume no bad faith on the part of Garland. Throughout his many years in public life, he has acted with integrity and independence, and at least based on what we know now, I see no basis for asserting otherwise here. I could be wrong—the history of the Justice Department unfortunately includes examples of situations where officials abused their power—but as my longtime readers know, I try to give subjects the benefit of the doubt. So I’m going to do that here, until specific evidence (beyond the fact that the search occurred) suggests otherwise.

Here’s another reason not to presume bad faith on Garland’s part: the decision to seek a search warrant for Mar-a-Lago was surely approved by other DOJ officials—most notably, FBI Director Christopher Wray. And Chris Wray, as many have noted, is a longtime Republican, appointed by none other than… Donald Trump. Had Wray viewed the search as a politically motivated abuse of power, as some supporters of Trump claim it to be, I suspect he would have resigned.

So this brings us to Monday’s search. Here are a few thoughts—some based on news accounts of the event, and some more speculative.

First, as reported by the New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal, it appears the Mar-a-Lago search was justified based on probable cause to believe that (1) a federal crime was committed relating to the possible mishandling of classified documents or information, and (2) evidence of such a crime could be found at Mar-a-Lago. It was not justified based on possible crimes arising out of the January 6 attack on the Capitol.

“Probable cause” is the standard that had to be met before U.S. Magistrate Judge Bruce Reinhart (S.D. Fla.) would have approved the warrant—because the warrant also had to be approved by a judge, not just DOJ officials. According to Trump lawyer Christina Bobb, the Mar-a-Lago warrant referred to the Presidential Records Act and possible violations of law over the handling of classified information. We have not seen the warrant itself, but Trump has a copy and can release it whenever he wants to (although he wouldn’t have copies of any affidavits in support of the warrant)

Second, even if the search warrant was justified based on document-related offenses, I suspect that Garland and his fellow DOJ officials are looking for—and maybe even expecting—evidence related to other, more serious crimes. I agree with former federal prosecutor Andrew McCarthy of the National Review:

There’s a game prosecutors play. Let’s say I suspect X committed an armed robbery, but I know X is dealing drugs. So, I write a search-warrant application laying out my overwhelming probable cause that X has been selling small amounts of cocaine from his apartment. I don’t say a word in the warrant about the robbery, but I don’t have to. If the court grants me the warrant for the comparatively minor crime of cocaine distribution, the agents are then authorized to search the whole apartment. If they find robbery tools, a mask, and a gun, the law allows them to seize those items. As long as agents are conducting a legitimate search, they are authorized to seize any obviously incriminating evidence they come across. Even though the warrant was ostensibly about drug offenses, the prosecutors can use the evidence seized to charge robbery.

I agree with McCarthy’s premise that prosecutors not infrequently seek a search warrant based on crime X in the hope that they might also find evidence of crime Y. And even if some critics might view that as an unseemly “fishing expedition,” there is nothing illegal about the practice.

Under the Fourth Amendment, a search warrant must “particularly describe the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized,” in order to “protect individuals from being subjected to general, exploratory searches.” But courts have explained that “the particularity requirement of the Fourth Amendment must be applied with a practical margin of flexibility,” and the so-called “plain view” doctrine “permits a warrantless seizure where (1) an officer is lawfully located in the place from which the seized object could be plainly viewed and must have a lawful right of access to the object itself, and (2) the incriminating character of the item is immediately apparent.”

Here’s an example. An officer with a warrant to search for evidence of counterfeit software came across child-pornography files. The defendant moved to suppress the child pornography, arguing that it wasn’t mentioned in the warrant; the court denied the motion, holding that the files were in “plain view.”

The same holds true here. If FBI agents looking for evidence of violations of the Presidential Records Act come across evidence related to January 6 crimes, the latter would likely be admissible. Or as Andrew McCarthy put it, “The ostensible justification for the search of Trump’s compound is his potentially unlawful retention of government records and mishandling of classified information. The real reason is the Capitol riot.”

Third, if the evidence seized from Mar-a-Lago winds up not supporting charges beyond the mishandling of classified information, then I do not believe the DOJ will prosecute Trump—and I do not believe the DOJ should prosecute Trump.

While the allegations about Trump’s mishandling of classified material and presidential records are egregious—most infamously, he stands accused of shredding documents and flushing them down the toilet—they are not sufficiently serious to justify such a divisive prosecution (which might just strengthen Trump politically, by allowing him to play the martyr and claim another “witch hunt”). And I do not believe that Garland would exercise his prosecutorial discretion to move forward with such a case, weighing the gravity of the alleged offenses against the consequences for the DOJ’s reputation, which would be viewed as an inappropriately political actor, and the consequences for the country, which would only be further polarized. (There’s a reason why “Civil War” was trending on Twitter earlier this week.)

Fourth and finally—and this might be my most controversial point—an argument can be made that the Mar-a-Lago search will end up as a “win-win” for both Merrick Garland and the Department of Justice. Consider three possible outcomes:

- The search turns up no significant evidence of any crimes.

- The search turns up evidence of only the mishandling of classified or otherwise protected documents or information.

- The search turns up evidence of crimes more serious than the mishandling of classified or otherwise protected documents or information, such as crimes related to (a) the January 6 uprising itself or (b) obstruction of the investigation into January 6, such as intimidating or otherwise tampering with witnesses.

In scenarios (1) and (2), I predict that Garland and the DOJ will execute their discretion not to prosecute. They might not discuss that decision—remember that former FBI director James Comey’s explanation of his non-prosecution of Hillary Clinton broke with DOJ protocol—but their choice would have the beneficial effect of giving political cover to President Biden vis-a-vis the Democratic Party’s left flank.

President Biden would be able to paraphrase his remarks introducing Garland as his AG nominee and say something like, “The Department of Justice doesn’t work for me. Its loyalty is not to me. Its loyalty is to the law, the Constitution, and the people of this nation. And in this case, the Department conducted an extremely thorough investigation—an investigation so thorough it included the unprecedented step of searching a former president’s personal residence—but ultimately decided not to bring charges. Attorney General Garland and FBI Director Wray—appointed by me and by former president Trump, respectively—concluded that it was not in the interest of justice to bring charges. And I respect their decision.”

Now, this outcome would leave many people unhappy. Many on the right would be unhappy that the search even occurred, and many on the left would be unhappy that Trump wasn’t indicted. But people in the middle—moderates, i.e., the folks who decide elections—might hear these words from Biden and find them reasonable.

Now let’s turn to scenario (3), and imagine that the Mar-a-Lago search produces strong evidence of serious crimes—evidence strong enough for Garland to conclude that he can prove grave federal offenses beyond a reasonable doubt. In this case, I think Garland would be willing to prosecute former president Trump.

And in this case, depending on the strength of the evidence and the seriousness of the crimes at issue, Garland would at least have a shot of persuading a majority of the American people that prosecution is justified. He might be able to pull together a national consensus like the one that formed in the wake of Watergate. He will never convince the MAGA crowd that prosecuting Trump is justified; to this crew, Trump’s infamous quip about being able to shoot someone in the middle of Fifth Avenue without losing support is sadly true. But I don’t think Garland is one to let Team MAGA overrule his prosecutorial prerogatives.

As U.S. attorney general, Merrick Garland is bound to uphold the due process of law—and one could argue here that the Mar-a-Lago search is exactly what was “due.” It enjoyed full legal justification because probable cause existed to believe the search could unearth evidence of federal crimes.

If it produces evidence of crimes that are insufficiently serious, then Garland doesn’t have to prosecute, and he won’t. But the American people can rest a little easier, knowing that potential crimes were duly investigated and that no man, even a former president, is above the law.

If it produces sufficiently strong evidence of crimes that are sufficiently serious, then Garland can and will prosecute. And both Donald Trump and the American people will get exactly what they are due: United States of America v. Donald John Trump.

First published in Original Jurisdiction

Author

David Lat Lawyer turned writer: Original Jurisdiction, http://davidlat.substack.com. Founder, AboveTheLaw/@ATLblog. Author, @SCOTUSambitions. Survivor, #coronavirus #COVID #ventilator.