When Tikanga Just Doesn’t Cut the Mustard

John Bowie, LawFuel publisher

There’s something exquisitely theatrical about radicals discovering, at the very moment of personal inconvenience, that the colonial court system is suddenly quite useful.

Mariameno Kapa-Kingi’s dash to the High Court after her ejection from Te Pāti Māori is a masterclass in ideological gymnastics.

Kapa-Kingi, for those who missed the Te Pāti Māori operatic show, is the MP who declared in Parliament that the Government was on a “mission to exterminate Māori.”

Her maiden speech referred to the court system that fails to recognise Maori sovereignty. The Cout system is racist and oppressive, designed to dispossess Maori of their rights, she has said.

Indeed she huffs and puffs and blows steam out of every aperture to express her profoundly felt disdain for the oppression and unfairness dispensed by the colonist court system under which she must live.

But when Kapa-Kingi found herself turfed out by Te Pāti Māori‘s National Council over allegations of misusing funds and bringing the party into disrepute where did this champion of tikanga turn?

Not to a hui on the marae. Not to the indigenous dispute resolution processes her party claims to hold sacred. Instead it was straight to the High Court at Wellington with a King’s Counsel in tow.

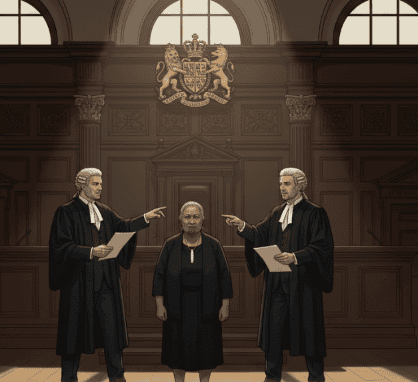

Allegations of nepotism flew in an almost hysterical way from, of all people, John Tamihere via his own silk, Davey Salmon KC. The nepo claims were repelled by Michael Colson KC for Kapa-Kingi. Two of the most expensive legal swords in the land were crossing blades over a party that routinely denounces exactly this sort of elite legal machinery.

It was the full colonial legal deluxe package – silk gowns, formal submissions, competing KCs earning by the minute while their activist party reverted to a form of political cannabilism by consuming their own.

Michael Colson helpfully explained that his client came to court “reluctantly,” preferring face-to-face discussions. When your preferred tikanga-based resolution involves being thrown out on your ear, those stuffy old colonial procedures about due process start looking rather civilized.

Justice Radich’s decision found “serious questions to be tried” about mistaken facts and procedural irregularities regarding her being unceremoniously thrown from the Te Pāti Māori fold. It was the sort of technical legal stuff that only matters in oppressive colonial courts. He granted interim reinstatement, noting she’d suffered “irretrievable prejudice” without it.

Co-leader Rawiri Waititi insisted they had tried everything before expelling her. “When tikanga hasn’t been able to do that, then we turn to the kaua.” The constitution, in other words. But when Kapa-Kingi didn’t like how the kaua worked out, she turned to something far more reliable – a High Court judge and two leading KCs.

This isn’t to deny Kapa-Kingi her legal rights. She is entitled, like any citizen, to go to court. The right exists because of the very system she and her political allies have spent years deriding as illegitimate. One cannot spend a career briefing against “colonial courts” and then, when the internal party knives come out, sprint for the nearest colonial judge.

Despite all the righteous and terribly fashionable chest-thumping rhetoric about indigenous justice systems and decolonizing the law, when the music stops and someone’s actual rights are on the line there is suddenly a line-march to the kauri-pannelled boardrooms and their KC inhabitants to pursue discovery, natural justice, the rules of evidence, and a judge with the power to issue binding orders.

Tikanga is splendid, but it doesn’t issue interim injunctions.

The legal system is condemned in theory because it’s fashionable to condemn it. In practice, when power, money, reputation or position is at stake, it becomes suddenly indispensable. Principles dissolve on contact with consequences.

The wider Te Pāti Māori implosion now looks set to drag through the courts in instalments. A public party devouring itself by private legal process. Each affidavit another chapter. Each hearing another taxpayer-funded encore. The substantive hearing is set for February, where no doubt we’ll hear more impassioned arguments about constitutional compliance and procedural fairness, all delivered in English, in a courtroom operating under Crown authority, applying principles developed over centuries of British legal tradition.

The revolution, it turns out, still needs KCs.

The system survives its critics not because it is perfect but because, when the shouting stops, it still works. Perhaps someone might gently suggest that if our legal system is good enough for Mariameno Kapa-Kingi when she needs it, it might just be good enough for the rest of us too.

But consistency has never been the strong suit of political theatre, and this particular show has several acts yet to run yet.