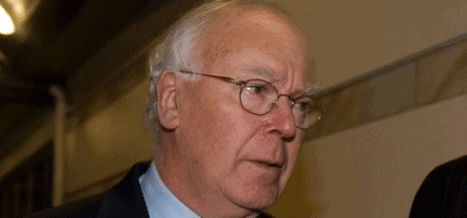

Queens Counsel Kristy McDonald, a colleague and close friend of Bruce Squire, writes about the remarkable cases and life of one of New Zealand’s top silks, who died on September 30

He was the only son of a Northland naval man who had fought in the Battle of the River Plate. He was the child of loving parents who brought their son up in the country with rules, discipline and a strong sense of principle, of right and wrong.

He was a young man who spoke of his fondness and respect for many of his teachers at Whangarei Boys’ High School, but not all. A talented sportsman – captain of the first XV and of the first XI.

>> See the latest legal roles on the LawFuel law jobs site

Pretty much in every sport he turned his hand to, he did well. Sport was important to him; rugby, particularly, was his great passion. Bruce Squire went on to become heavily involved in rugby disciplinary proceedings, developing much of what we know as the modern rugby judicial process.

He travelled extensively to Sanzar meetings and World Cup games, chairing many crucial rugby disciplinary matters, such as the infamous incident when Sean Fitzpatrick had his ear bitten in 1994. And he made good friends across the world through that work. He later also became involved in racing judicial work, and again – seemingly effortlessly – delivered complex sporting judicial decisions, always reflecting fair play but without killing the sport.

Sports Involvement

Competition, physicality, discipline, teamwork, fairness were things Bruce learnt as a young man and they continued to influence and shape his entire legal career.

But, despite his protestations to the contrary – and we argued about this repeatedly – he had a fierce intellect and an ability to digest and analyse information better than anyone else I know.

He started practice in Invercargill after he and Virginia were married, and there he began working as a prosecutor. He learnt well, understanding what it meant to carry that responsibility, that burden, and the importance of strength on the one hand and fairness on the other.

He was thrown in at the deep end, doing serious criminal trials early in his career, and that would have had a big impact on him. Bruce understood about fairness, kindness, the frailty of life, of the importance of people in all that we do.

He and Virginia moved to Wellington in early 1976, and Bruce started work at the Crown Law Office. Sir Richard Savage was the solicitor-general at that time, a formidable man, like Bruce, strong, principled, kind and fair. Bruce admired him enormously, and Richard was a true mentor for him. Sir Richard told me once that he thought Bruce was one of the finest lawyers he’d known.

From the time Bruce was at Crown Law and subsequently, he was involved in some of the most significant litigation for the Crown. The Clowns case, concerning protesters beaten by police during the 1981 Springbok tour, was a seminal event. He was also involved in the Rainbow Warrior incident, the Arthur Allan Thomas inquiry, and the significant immigration decision of Benipal v the minister of immigration.

The Ortiz case, involving the government seeking the return of Māori artefacts from the UK in 1973, took Bruce to London, where he appeared in the High Court and Court of Appeal – one of only a few New Zealand lawyers to do so without being formally admitted in the UK courts.

Then there was the infamous Plumley-Walker trial that Bruce prosecuted in Auckland, the Winebox Inquiry that lasted for years, and the prosecution of art forger Carl Goldie, as well as many high-profile murder trials.

What followed for Bruce was a very successful practice at the independent bar.

When I met him he seemed to be the most important lawyer in New Zealand. He seemed to have been involved in every important case, and worked more hours than the day had. But he still had time to help others. That was something he did for young lawyers throughout his career. He was always on the phone providing advice, helping other lawyers shape their arguments.

There were many times when he advised and represented lawyers who had lost their way professionally. He helped them with their driving charges, their Law Society issues and more serious problems, and he provided whatever it was they were missing – friendship, a strong hand and an anchor.

Taking Silk

Bruce took silk in 1992. What followed were more years of high-profile and important cases: murder trials, fraud trials (South Canterbury Finance), fisheries cases, appeals, complex legal arguments, important legal precedents. The law reports are full of his cases, both successes and losses. He wore his successes with humility, but he didn’t like losing!

Bruce also became a fine defence counsel. He was a formidable advocate for his clients, and every case he took was as important to him as the last. It didn’t matter how small it was, which court it was in, or who it was for. Many were done pro bono or for heavily reduced fees.

That’s what he was like. He didn’t seek fame or glory; indeed, he actively shunned it. Despite my urging that just occasionally he might like to take some credit for these things, he never did. It was always about the individual. He cared deeply for his clients.

Man of Dignity

I can recall as a young prosecutor appearing alongside Bruce, watching his professionalism, his dignity, noticing that you didn’t need to be flamboyant or showy to have a jury trust you. You just needed to be honest and fair.

One thing that struck me on our first appearances together was how, when he stood up to introduce us to the court, he always put my name first – “Ms McDonald and I appear”, never “I appear with Ms McDonald”. He always announced his junior before himself.

But he was human. He had his frailties and his shortcomings. He could be abrasive and too direct at times, and he took humility and his rejection of self-importance to a point that was sometimes counterproductive.

He was unforgiving if he felt those he had trusted and respected had let him down. There was no going back, as Bruce had no time for pomposity, gravitas, pretension or duplicity.

That is what made him such a fine lawyer – his humility, his honesty, his fearlessness, his overwhelming and steadfast commitment to principle, and his unfailing generosity. Those characteristics are learnt from your parents, but they also come from real experience with real people, from all walks of life.

Bruce was one of those special lawyers: he observed, he listened and understood people, he saw their distress, their worry, their fear, their families – and that made him a fine advocate, a brilliant cross-examiner, and ultimately a thoroughly decent man.

He was also a most generous man, generous with his time and with whatever he could give. The first to pay for coffee or lunch, always ready to give to whatever charity made a call to him – and it was non-judgmental generosity. It didn’t come with strings.

Almost without exception friends and colleagues have said, “He was such a principled person”, then they’ve gone on to tell stories of ringing him to check whether a decision they’d made was ethical, or a judgment they’d made had been right.

Bruce knew how to make principled decisions. It wasn’t just a word to him, it was everything. Being principled isn’t easy. The right decisions are almost always the hard ones – but they are also most often the obvious ones. Once you learn to ignore what you want the decision to be, then it becomes much easier because you remove your personal interest from the process.

It’s not about what you want to do; it’s about what you should do. There were no shades of grey when it came to being principled. You had to be able to look yourself in the mirror at the end of the day, he would say, and do the right thing.

He was a feminist, which may come as a surprise. Not once in 35 years did he ever suggest I couldn’t or shouldn’t handle any matter. Not once in 35 years did he ever talk over me or patronise me (other than in jest); not once in 35 years did I ever feel he thought I wasn’t up to it because I was a woman.

Bruce was extraordinarily sensitive and kind. He was a soft-hearted man. He was unfailingly patient and generous to the various secretaries/PAs and employees we had over the years, and rarely got cross or impatient.

Bruce Squire leaves an impressive legacy of dedication to his clients and an enviable reputation for intelligence, honesty and integrity. His memory, though, will be held close for a very long time by a handful of nearest and dearest.

He is survived by his wife Virginia, daughter Caroline and son Martin.